Public Companies Merton Probabilities of Default with public data

The views and opinions expressed in this post are solely my own and do not necessarily reflect those of my employer. This content is for general informational purposes only and does not constitute professional advice.

This is a simplified but (hopefully) useful explanation of what the Merton probability of default (PD) model is and why it matters. Let’s start with why this is needed and then dig into how to calculate it for Public Companies, specifically US publicly traded companies.

Why PD

Credit risk assessment is how lenders estimate the cost of lending, effectively, the price of taking risk. For regular American consumers, this would be the FICO score. In essence, the FICO score is a retail-level version of what banks estimate internally as a Probability of Default (PD).

This assessment implies multiple things for lenders, such as the price you pay for a mortgage, a way to be prepared for bad times (i.e., save cash as anyone would save for a rainy day), and also a way to report their financial health to regulators.

At this point, what we need to know is the probability of default (PD) of the borrower, which is a binary outcome given by a Bernoulli distribution, to end up estimating some expected losses.

And I feel that calculating monetary expected losses is way more straightforward than, let’s say, medical diagnostics. The reason I am saying this is because I am sure there are lots of factors to take into account to make a decision or evaluate when working with the outcome of a model that diagnoses. With money, it’s clear: $PD \times \text{Amount} = \text{Expected Value}$. Period. If you have this right, you can forecast, and therefore make money.

This is where calculations like the Merton score or the ratings given by the agencies come into play. One thing that is important to note is that in credit risk, properly sorting the borrowers by their PD is usually the most important part.

The reason I am saying this is because, as I previously mentioned, this PD is used in different areas in finance, and perhaps this PD is not as important as your ability to use it in different ways, “tweaking it.” Although this might sound weird, we are talking about risk, meaning this has to be managed, and risk has to be taken. This is not an exact science nor deterministic, so yes, things can be tweaked.

Why sorting? Well, if you can sort, you can create buckets to manage things in groups, and if you have a good enough estimation of that bucket, you are good enough to do your forecasts and manage your risk as you want.

Now, there are other things to take into account that make this trickier and probably different to modeling in other areas. One that was also hard to digest for me, besides the tweaking part, is the Point-in-Time (PIT) vs. Through-the-Cycle (TTC). This is again a “tweak” of the estimation. The basic idea here is that you can estimate PDs either using long-term historical data of borrowers or you can take a photo of what is exactly happening now in the world and the borrower to estimate the PD. This also blew my mind, because hold on, if we are calculating the PD in one year, why does it matter how you are calculating that? I mean, I want the PD, and I want it to be right (whatever that means as you can’t draw multiple experiments for that exact borrower, but you get what I mean, I want it to calculate expected losses appropriately along my portfolio).

Ok, so why these different ways to calculate the PDs? Because again, we want to manage risks here, and it’s not the same what you want to use to price the loans, what you want to use to save, and what you have to report to regulators, right? I mean, if it is for example for your savings to be able to go through rougher times, probably you don’t want these to be super volatile and be moving money around when what you really want is a long-term estimation of unexpected losses and be able to overcome this. Here, most probably, you want a Through-the-Cycle estimation.

On the other hand, you absolutely want a Point-in-Time (PIT) estimation for loan pricing. If the economy is great right now, your PIT PD will be low. This allows you to offer a lower, more competitive interest rate to that borrower today. If you used your high, conservative TTC estimate, your price would be too high, and you’d lose that customer to another bank. What if things change and go south? Well, there is where all the other process looking for long-term consequences come into play.

In short: PIT PDs move with the economic cycle and are used for pricing and short-term forecasting, while TTC PDs smooth out those cycles and are used for capital and provisioning.

Merton

Now enters the Merton model, a structural approach that links a firm’s balance sheet to market-implied default risk. In a super simplistic but understandable way, Merton calculates the distance between Assets and Liabilities and translates that distance into PDs. The closer the liabilities get to assets, the higher the PD gets. If liabilities are greater than assets, well, you are screwed, you can’t face your payments and you are defaulted. So by nature, and although never used raw, it is a clear PIT model.

Defaulting in companies is not as simple as it seems. It is not like one day the company defaults and then it disappears from the earth. Default isn’t an instant collapse but a contractual event, missing a payment, breaching a covenant, or triggering restructuring. From a lender’s perspective, the key point is: when do I stop getting paid?

So what is it then? It depends again, but probably if you are a lender you would want to define a default as something like missing a payment , because that is what you care about. So the first payment it is missed, it is considered a default, because that might be you.

I said this is simplistic, and it is, because one of the biggest hurdles to calculating PDs is the timeframe. What is the time this PD covers? Is it going to default in 1 day, 1 year, or 1 decade? Well, obviously it is a completely different calculation, and here is where things get complicated.

So it seems that we need a function of the asset value, asset volatility, and time to give us this distance to default (DD). The issue isn’t that the function doesn’t exist (it does), but that two of its key inputs, the asset value and asset volatility, are not directly observable. But, we do have a function that calculates the equity value (market capitalization of the company), uses these same inputs, and is observable. So, we can use it to derive what we need.

Options analogy

A useful trick to handle all this is that intuitively, we can treat a company’s equity like a call option on its assets. That is exactly what Merton does.

Let’s now introduce options and how to calculate their value. An option in finance is the right but not the obligation to execute a deal in the future, let’s say buy an asset in one year for a price agreed today. Now, the payoff of this product is like this: if the price is above the agreed price, you buy the asset at the agreed price and sell it at market price, the margin between the agreed and market price in the future is your profit. If it is below, you make 0 and lose all the money you paid for this product.

This payoff can be calculated as:

\[\max(S_T - K, 0)\]where $S_T$ is the price as of $T$ (or spot price) and $K$ is the agreed price (or Strike).

This is what is called a European call option, which is the simplest type of option in finance, and what we will use in our framework for credit and PDs.

The expected value of this type of deal is rather hard to calculate, or at least is not straight forward. Somehow you have to calculate how the distribution of the price of the underlying asset is going to be in one year, and see how much of that is above the agreed price and how much below, and from there you can calculate the value today of that deal. This is hard to calculate but it is known and there is a way to solve it analytically. It is based on stochastic calculus and the famous Black-Scholes formula.

From options to credit

Merton realized that the structure of a firm’s balance sheet mirrors an options contract. Here’s the mapping:

- Underlying Asset: The total market value of the firm’s assets ($V_A$).

- Strike Price ($K$): The face value of the firm’s debt (liabilities) that must be repaid at a future time $T$. This is the “default point” ($L$).

- Option Holder: The firm’s shareholders (equity owners).

- Time to Maturity ($T$): The time until the debt is due (e.g., 1 year).

Now, there are two possible outcomes here:

- If $V_A(T) > L$ (Assets are greater than Liabilities): The shareholders “exercise their option.” They pay off the debt holders (pay the “strike price” $L$) and get to keep the remaining asset value, which is $V_A(T) - L$.

- If $V_A(T) \le L$ (Assets are less than or equal to Liabilities): The firm defaults. The shareholders “let the option expire worthless.” They have limited liability, so they lose their entire investment but owe nothing more. Their payoff is $0$.

This payoff structure here is $\max(V_A(T) - L, 0)$, the same as an European option, so we can start building from here.

The Two-Equation System

So we know what we want: the unobservable Asset Value ($V_A$) and Asset Volatility ($\sigma_A$).

And we know what we have: the observable Equity Value ($E$) (the market cap) and Equity Volatility ($\sigma_E$) (the stock’s volatility).

The genius of the Black-Scholes-Merton model is that it provides two distinct equations that link all four of these variables. This creates a system of two equations with two unknowns, which can then be solved.

-

The Black-Scholes Equation for Equity Value: This is your option analogy in formula form. It states that the value of the firm’s equity ($E$) is equal to the value of a call option on its assets ($V_A$). \(E = V_A N(d_1) - D e^{-rT} N(d_2)\)

-

The Equation for Equity Volatility: The model also provides a second, complex relationship linking the volatility of the equity ($\sigma_E$) to the volatility of the assets ($\sigma_A$). \(\sigma_E = \left(\frac{V_A}{E}\right) N(d_1) \sigma_A\)

(Where $N(\cdot)$ is the cumulative standard normal distribution, and $d_1$ and $d_2$ are intermediate probability terms from the Black-Scholes formula.)

You absolutely do not need to solve this by hand. Conceptually, you just feed the two equations and your knowns ($E$, $D$, $\sigma_E$, $r$, $T$) and find the two unknowns ($V_A$ and $\sigma_A$) that make both equations true.

Distance to Default (DD) and Final PD

Once we have $V_A$ and $\sigma_A$, the final step is simple.

The Distance to Default (DD) is calculated. This is effectively a “z-score”, it measures how many standard deviations the firm’s assets ($V_A$) are away from the default point ($D$). This is the famous $d_2$ term from the Black-Scholes formula.

\[\text{DD} = \frac{\ln(V_A / D) + (r - 0.5 \cdot \sigma_A^2) \cdot T}{\sigma_A \cdot \sqrt{T}}\]The final Probability of Default (PD) is simply the statistical probability of $V_A$ falling below $D$, which is given by $N(-DD)$.

\[\text{PD} = N(-\text{DD})\]This final $PD$ is the model’s 1-year, market-implied, Point-in-Time probability that the firm will default.

Data Requirements for the Merton Model

The Merton model’s elegance comes from its use of observable market and accounting data to solve for unobservable firm variables (like its total asset value and asset volatility). So for public US companies, to calculate the probability of default over a specific time horizon (typically 1 year), you need these key pieces of data:

| Data (Model Input) | Functional Part (Explanation) | Typical Source |

|---|---|---|

| Equity Value (E) | The total market value of the company’s stock, known as Market Capitalization. This is the observable value of the firm’s equity, which the model treats as a call option on the firm’s total assets. | Financial Data Provider (e.g., Bloomberg, Refinitiv, Polygon.io, Yahoo Finance). This is the stock price multiplied by the number of shares outstanding. |

| Face Value of Debt (D) | The “strike price” or default point. This represents the book value of the firm’s liabilities that must be repaid. It is often estimated using a combination of short-term and long-term debt. | Public Company Filings (e.g., SEC 10-K/10-Q reports). Analysts typically sum short-term liabilities and a portion (often 50%) of long-term liabilities. |

| Equity Volatility ($\sigma_E$) | The annualized volatility (standard deviation of returns) of the company’s stock price. This represents the “riskiness” of the equity, a key input for the option pricing formula. | Calculation from Historical Price Data. This is derived from the daily stock price time series, typically calculated over a 1-year (or 252-trading day) rolling window. |

| Risk-Free Rate (r) | The interest rate on a risk-free asset (like a government bond) that matches the model’s time horizon. It’s used to discount the future value of the debt to its present value. | Central Bank or Government Data (e.g., U.S. Treasury, FRED). For a 1-year PD, the 1-year U.S. Treasury bill rate is a common choice. |

| Time to Maturity (T) | The time horizon over which you are calculating the probability of default. | An Model Assumption. This is not a data point but a parameter chosen by the modeler. For most credit risk applications, this is set to 1.0 (for a 1-year PD). |

Project Application: Tracking PD Over Time

This article isn’t just theoretical; it’s the foundation for this (link here) data analysis project.

The core of the project is to calculate the 1-year Merton PD for each company, not just at one time, but for every single quarter they release a financial report. This creates a PD time series for every company, allowing us to track their market-implied credit risk over time.

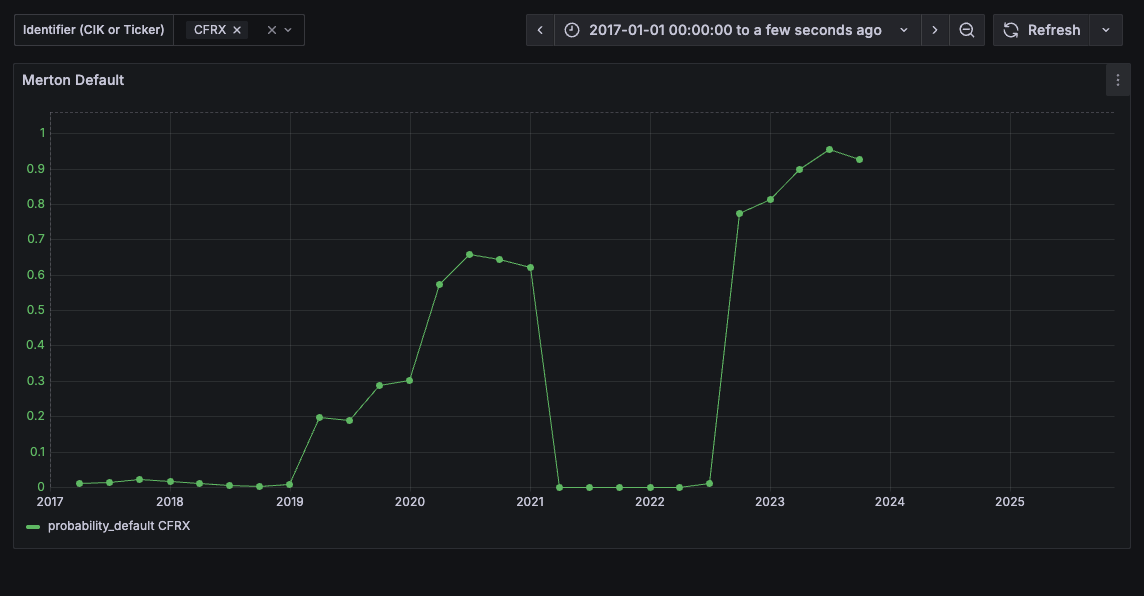

But does the model work? The most important test of a default model is simple: do defaulting companies actually show high PDs before they default?

The answer is yes. The results clearly show a trend of increasing PDs leading up to their default. For example, a company like ContraFect Corporation (CFRX) filed a petition for liquidation on December of 2023 (see here), and see how its Merton PD looks like below.

Is the goal of this project to predict defaults with Merton scores? Absolutely not, this is just to showcase that with, almost, all public data, we can create a pretty solid base for a commercial credit risk framework. For example, these scores or PDs can be used as part of a bigger framework, where these are used to maybe estimate PDs using other financial information (we could use other financial statements from EDGAR) and then create a “real” PD estimator that we can later use with our portfolio of commercial loans. We can add macro economic information, make it TTC, … All sort of things.

The data I used and that is plotted is also public. All but the time series of market capitalizations that is from a market data provider that does not allow to make their data public.

The public dataset

Here is the dataset. This is a CSV file with below columns so you can play with the data and maybe create your own commercial models.

Other useful data is this defaulted companies database, (UCLA-LoPucki Bankruptcy Research Database (BRD). You can use this data to validate Merton PDs, enrich the model, …

And again, you will only need to add the market capitalization (which represents the Equity Value $E$) time series for each company and quarter as that is not free (maybe you can derive it from the PD? Not sure).

Here is an explanation of the columns in the public file:

| Column | Explanation | Type |

|---|---|---|

cik |

Central Index Key; a unique identifier for each company from the SEC. | Identifier |

period_end |

The “as-of” date for the quarterly financial report (e.g., ‘2023-12-31’). | Identifier |

ticker |

The company’s stock ticker (e.g., ‘CFRX’). | Identifier |

debt |

The Input Face Value of Debt ($D$), calculated from SEC filings. | Model Input |

annual_vol |

The Input Equity Volatility ($\sigma_E$), calculated as a 252-day rolling volatility. | Model Input |

treasury_10y |

The Input 10-year risk-free rate ($r$) for that period, sourced from FRED. | Model Input |

merton_score_dd |

The Calculated Output Distance to Default (DD) from the model. | Model Output |

probability_default |

The Calculated Output 1-year Probability of Default (PD) from the model. | Model Output |

asset_value |

The Calculated Output (unobservable) firm Asset Value ($V_A$) solved by the model. | Model Output |

asset_volatility |

The Calculated Output (unobservable) firm Asset Volatility ($\sigma_A$) solved by the model. | Model Output |

Code to Run the Model

Here is the complete Python script you can use to load the public dataset, merge it with your own market cap data, and re-calculate the Merton PDs.

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

from scipy.stats import norm

from scipy.optimize import fsolve

import warnings

# This function is the core of the model.

# It takes 'vars' [V_A, sigma_A] and knowns (E, D, r, sigma_E, T)

# It returns the 'errors' of the two equations, which fsolve tries to minimize to zero.

def merton_solver(vars, E, D, r, sigma_E, T):

"""

Solves the Merton model's system of two non-linear equations.

'vars' is a list [V_A, sigma_A] (the two unknowns)

"""

V_A, sigma_A = vars

# Constraint to prevent math errors (e.g., log(0), sqrt(neg))

# If solver tries non-positive values, return a large error

if V_A <= 0 or sigma_A <= 0:

return [1e9, 1e9]

# d1 and d2 from Black-Scholes formula

# These are intermediate terms

with warnings.catch_warnings():

warnings.simplefilter("ignore") # Ignore log/sqrt warnings during solve

d1 = (np.log(V_A / D) + (r + 0.5 * sigma_A**2) * T) / (sigma_A * np.sqrt(T))

d2 = d1 - sigma_A * np.sqrt(T)

# --- The Two Core Equations ---

# Eq 1: Value of equity (E) as a call option on assets (V_A)

# E = V_A*N(d1) - D*exp(-rT)*N(d2)

# We set it as (LHS - RHS) = 0

eq1 = E - (V_A * norm.cdf(d1) - D * np.exp(-r * T) * norm.cdf(d2))

# Eq 2: Relationship between asset volatility (sigma_A) and equity volatility (sigma_E)

# sigma_E = (V_A / E) * N(d1) * sigma_A

# We set it as (LHS - RHS) = 0

eq2 = sigma_E - (V_A * norm.cdf(d1) / E) * sigma_A

return [eq1, eq2]

def calculate_pd_row(row):

"""

Calculates Distance to Default and PD for a single row.

"""

E = row['market_cap']

D = row['debt']

r = row['treasury_10y'] / 100.0

sigma_E = row['annual_vol']

T = 1.0 # Assume a 1-year time horizon

if pd.isna(E) or pd.isna(D) or pd.isna(r) or pd.isna(sigma_E):

return np.nan, np.nan, np.nan, np.nan

# Initial guess for [V_A, sigma_A]

# We can start by guessing Asset Value = Equity + Debt

# and Asset Volatility is related to Equity Volatility

initial_guess = [E + D, sigma_E * E / (E + D)]

try:

# Use fsolve to find the roots (V_A, sigma_A) of the merton_solver function

with warnings.catch_warnings():

warnings.simplefilter("ignore")

solved_vars, _, exit_flag, _ = fsolve(

merton_solver,

initial_guess,

args=(E, D, r, sigma_E, T),

full_output=True

)

if exit_flag != 1:

return np.nan, np.nan, np.nan, np.nan

V_A, sigma_A = solved_vars

if V_A <= 0 or sigma_A <= 0:

return np.nan, np.nan, np.nan, np.nan

# Now that we have V_A and sigma_A, we can calculate the Merton Score (DD)

# and Probability of Default (PD)

# The Merton Score (Distance to Default) is the 'd2' value

distance_to_default_d2 = (np.log(V_A / D) + (r - 0.5 * sigma_A**2) * T) / (sigma_A * np.sqrt(T))

# The Probability of Default is N(-d2)

pd = norm.cdf(-distance_to_default_d2)

return distance_to_default_d2, pd, V_A, sigma_A

except Exception as e:

return np.nan, np.nan, np.nan, np.nan

def run_merton_calculation(public_data_path, market_cap_path):

"""

Main function to load data, merge market cap, and run the Merton model.

"""

print(f"Loading public data from: {public_data_path}")

try:

df = pd.read_csv(public_data_path)

except FileNotFoundError:

print(f"Error: Public data file not found at {public_data_path}")

return None

df['period_end'] = pd.to_datetime(df['period_end'])

# --- THIS IS THE STEP YOU MUST COMPLETE ---

# Load your private market cap data.

# It MUST have 'cik', 'period_end', and 'market_cap' columns.

print(f"Loading market cap data from: {market_cap_path}")

try:

mc_df = pd.read_csv(market_cap_path)

except FileNotFoundError:

print(f"Error: Market cap data file not found at {market_cap_path}")

print("To run this code, you must provide a CSV with market cap data.")

return None

mc_df['period_end'] = pd.to_datetime(mc_df['period_end'])

print("Merging market cap data...")

df = pd.merge(df, mc_df[['cik', 'period_end', 'market_cap']], on=['cik', 'period_end'], how='left')

required_cols = ['market_cap', 'debt', 'treasury_10y', 'annual_vol']

if not all(col in df.columns for col in required_cols):

print(f"Error: DataFrame is missing one or more required columns. Need: {required_cols}")

return None

print("Calculating Merton Score (DD) and Probability of Default (PD)...")

df[['merton_score_dd', 'probability_default', 'asset_value', 'asset_volatility']] = df.apply(

calculate_pd_row, axis=1, result_type='expand'

)

print("\nCalculation complete.")

return df

if __name__ == "__main__":

# --- UPDATE THESE FILE PATHS ---

PUBLIC_DATA_FILE = 'public_merton_data.csv'

MARKET_CAP_FILE = 'market_cap.csv' # Your file with the market caps

# It MUST have 'cik', 'period_end', and 'market_cap' columns.

results_df = run_merton_calculation(PUBLIC_DATA_FILE, MARKET_CAP_FILE)

if results_df is not None:

print("\n--- Final DataFrame Head ---")

print(results_df.head())