Playing with genetic algorithms in python

Edit: This post made it to the front page of Hacker News! You can find the discussion here.

A long long time ago I was young and going to school to attend a Computer Science program. It was so long ago that the data structures course was done in C++ and Java was shown to us as the new kid on the block.

Something I learned in CS that sticked in my head were Genetic Algorithms. I guess the reason was that GA were one of the first (and few) applied things I saw in CS and it seemed to me a simple, intuitive and brilliant idea. Today I was bored at home and I decided to play a little bit with it.

GAs are a search technique that is inspired in biological evolution and genetic mutations which are used to purge certain parts of the search space. This is done encoding the nodes in the space into a genetic representation and using a fitness function to evaluate them.

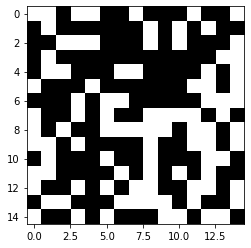

I started implementing a useless but I think illustrative example of GAs which is generating a sequence of random bits and then search for it. Plotting it as an $nxn$ matrix makes it is easier to visualize and debug the process.

img = np.random.randint(2, size=(15,15))

plt.imshow(img, cmap=plt.cm.gray)

plt.show()

This is a 15x15 array, so 225 bits and therefore a space of 2^225 possible combinations. Next I define the fitness function which is nothing more than the amount of bits of the image have the same value. In Numpy it would be:

def score(matrix1, matrix2):

return (matrix1 == matrix2).sum()

The genetic algorithm implementation per se (the fitness function, crossover and mutation) is implemented below, where the parameters population is the initial population and mutations are the percentage of mutated bits.

def ga(array, population, mutations):

def score(matrix1, matrix2):

return (matrix1 == matrix2).sum()

rows = array.shape[0]

columns = array.shape[1]

mid = rows//2

mem = np.random.randint(2, size=(2 * population, rows, columns))

scores = np.zeros((2 * population))

bottom = list(range(len(mem)))

for i in range(1000000):

# When initialized bottom will contain a set of random individuals. Later it will be

# the bottom of the list of individuals sorted by score

for k in bottom:

scores[k] = score(mem[k], array)

# Check if the solution has been found

max_score = np.argmax(scores)

if scores[max_score] == rows * columns:

print(i)

plt.imshow(mem[max_score], cmap=plt.cm.gray) # use appropriate colormap here

plt.show()

break

# Select the population of individuals according to the score function

top_n_scores = np.argpartition(scores, population)

top = top_n_scores[population:]

bottom = top_n_scores[:population]

# Create #population new elements from the crossover and mutation

for j in range(population):

# Crossover -> Select parents from the top individuals

#

# I tried this with random.choice or just picking a random position from the list and

# the next one. The result is the same for both but way faster

# with the latter option.

# The reason it still works might be either because of the randomization of the initial

# population or maybe the implementation of argpartition? or both?

r = random.randrange(len(top))

idx = [r, (r+1)%len(top)]

parents = [top[idx[0]],top[idx[1]]]

mem[bottom[j]][0:mid] = mem[parents[0]][0:mid]

mem[bottom[j]][-(mid+1):] = mem[parents[1]][-(mid+1):]

# Mutation -> Mutate the bits

#

# The random choice of the bits to mutate is the most costly of the implementation

# It seems there has to be some way to speed up this

idx = np.random.choice([0,1], p=[(1-mutations), mutations],size=(rows,columns))

mem[bottom[j]] = abs(mem[bottom[j]] - idx)

With some manual testing and trial error I ended up with an initial population of 500 and a mutation of 0.5% as the fastest way to find the array of bits, which finishes in approximately 160 iterations and 3 seconds in my computer. Even the experiment not making sense seems pretty good to me taking into account that the space is 2^225 and it can be implemented with few lines of code.

The entire implementation can be found here

Next I wanted to try something more useful, solving mastermind with 6 colors and 4 pegs, the original game had to be solved with 12 moves.

The implementation is similar to the previous one, mostly changing the score function. To count the number of evaluated choices I memoize the score function.

My best approach is a population of 2, and mutate 1 out of 4 pegs, with an average of ~36 evaluateed choices, so three times more than what would be the 12 choices of the original game. Something interesting is that with only crossover and mutation the information regarding the pegs with the correct color but not in the correct spot does not seem to be relevant.

The entire implementation can be found here

def ga(array, population, mutations):

score_memoization = {}

def score(board, choice):

key = tuple(choice)

if key in score_memoization:

return score_memoization[key]

tmp_board = board.copy()

in_place = 0

in_place_list = set()

same_color = 0

for i in range(len(choice)):

if choice[i] == board[i]:

in_place += 1

in_place_list.add(i)

tmp_board[i] = -1

for i,c in enumerate(choice):

if i not in in_place_list and c in tmp_board:

same_color += 1

# In correct place and correct color

#score = (2 * in_place) + same_color

# Only in correct place

score = in_place

score_memoization[key] = score

return score

mid = 4//2

mem = np.random.randint(6, size=(2 * population, 4))

scores = np.zeros((2 * population))

bottom = list(range(len(mem)))

for i in range(1000000):

# When initialized bottom will contain a set of random individuals. Later it will be

# the bottom of the list of individuals sorted by score

for k in bottom:

scores[k] = score(array, mem[k])

# Check if the solution has been found

max_score = np.argmax(scores)

if scores[max_score] == 8:

return i, len(score_memoization)

# Select the population of individuals according to the score function

top_n_scores = np.argpartition(scores, population)

top = top_n_scores[population:]

bottom = top_n_scores[:population]

# Create #population new elements from the crossover and mutation

for j in range(population):

# Crossover -> Select parents from the top individuals

#

# I tried this with random.choice or just picking a random position from the list and

# the next one. The result is the same for both but way faster

# with the latter option.

# The reason it still works might be either because of the randomization of the initial

# population or maybe the implementation of argpartition? or both?

r = random.randrange(len(top))

idx = [r, (r+1)%len(top)]

parents = [top[idx[0]],top[idx[1]]]

mem[bottom[j]][0:mid] = mem[parents[0]][0:mid]

mem[bottom[j]][-(mid):] = mem[parents[1]][-(mid):]

# Mutation -> Mutate the bits

#

# The random choice of the bits to mutate is the most costly of the implementation

# It seems there has to be some way to speed up this

idx = np.random.choice([0,1,2,3,4,5,6], p=[(1-mutations), mutations/6,mutations/6,mutations/6,mutations/6,mutations/6,mutations/6],size=(4))

for k in range(len(idx)):

mem[bottom[j]][k] = (mem[bottom[j]][k] + idx[k])%6